The Budget and not much more...

This Week In Data #110

The biggest takeaway from the budget was the significant increase in tax exemptions. From the current no tax till ₹7 lakhs of income to the proposed no tax till ₹12 lakhs of income is a significant change. For the financial year 2022-23, around 34 million individuals filed tax returns reporting income above Rs 5.5 lakhs (we don’t have the exact number of people with incomes above ₹7 lakhs). And in the last two years, the number would have increased by ~10-15%. So, ballpark of around 40 million people can potentially benefit from the higher tax exemption.

Of course, the quantum of benefit will not be the same for everyone and will depend on whether you are migrating from the old tax regime (and had exemptions) or the new tax regime. And of course, for some (especially folks with large HRAs), migrating to the new tax regime will not make sense even at these new rates. So, everyone’s mileage will of course differ – some will benefit more and some less, but what matters is the aggregate. The government expects this higher exemption to cost the exchequer ₹1000bn or 0.3% of GDP. So, if we assume, around 30 million people benefit from this higher exemption, it translates to ~₹33k per person. For reference, India’s per capita GDP is ₹2.4 lakhs. So both at an individual level and in aggregate, this is a material benefit.

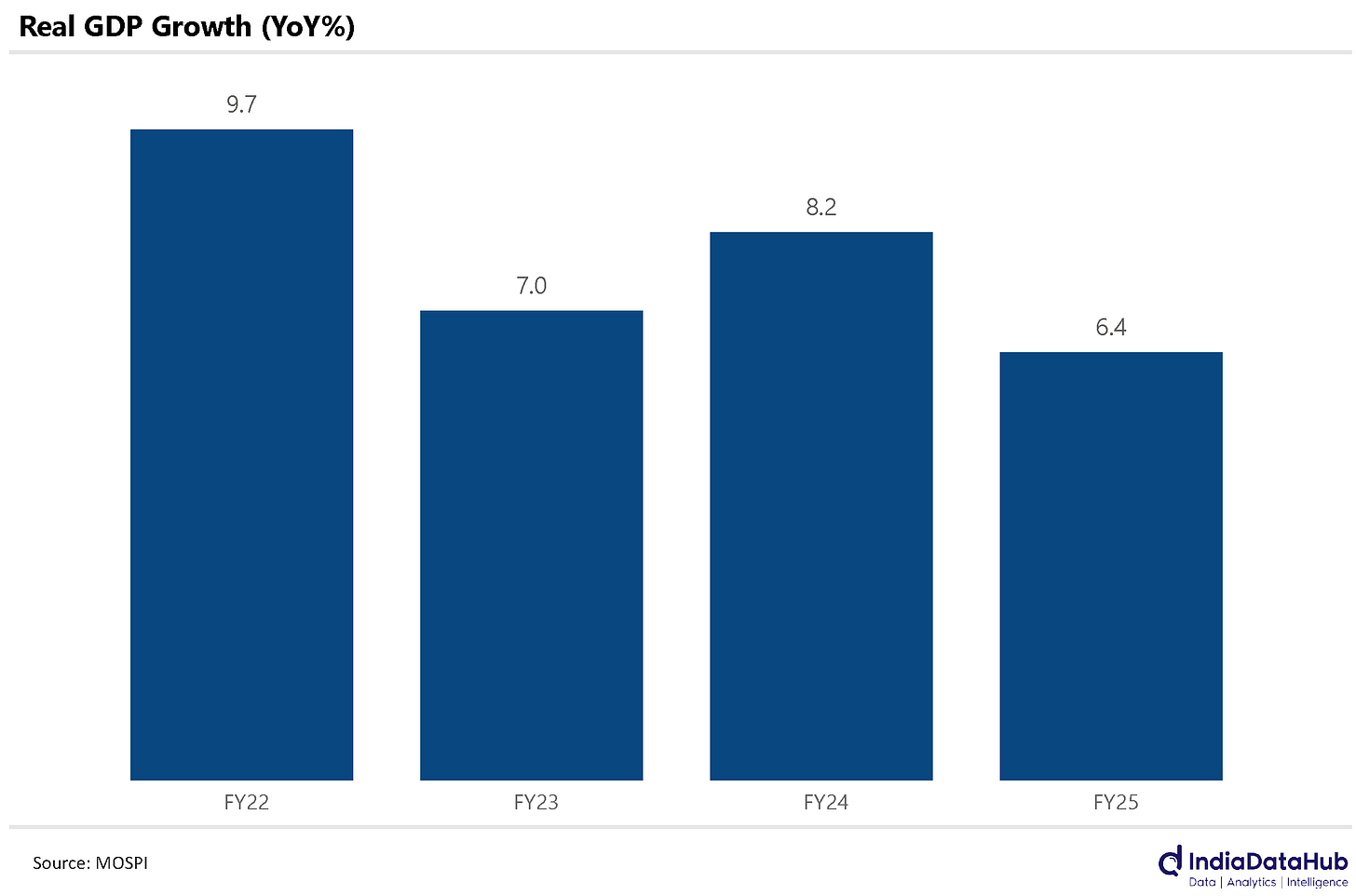

So, this should boost consumption and in turn GDP growth and eventually trickle down to other sectors of the economy through the multiplier effect. It should result in some upgrade to FY26 GDP growth estimate (which in FY25 has fallen to the lowest since the pandemic) as well as for some of the consumer goods companies – possibly the consumer durables companies as the quantum of savings is the sweet spot for them. Of course, for that people have to go and spend the money in a shopping mall or on an e-commerce platform rather than listening to their financial advisors and starting an SIP or paying down their debt. For we might run into the paradox of thrift in that case 😊

There is another positive angle to these tax changes. It will push more people towards the new tax regime which is bereft of (almost) any exemptions. And to give up those exemptions, people get to enjoy fairly liberal tax slabs and rate structure. Philosophically, this reduces one of the distortions of our tax policies where people’s investment decisions were guided by tax policy. Far too many people have bought a house just because they can offset the interest expense against their salary income. Far too many people have bought a non-term life insurance policy just because the larger premium helps them meet the 80C tax exemption limit. Dr Vijay Kelkar, one of the most eminent bureaucrats and intellectuals we have had in recent years, was one of the early proponents of this approach for individual taxation – eliminate exemptions and have liberal tax slabs and rates. As an aside, this book by Dr Kelkar and Ajay Shah on policy making in India is a delight to read.

Normally in the budget, the expenditure profile is the key point of focus. However, that has not been the case this year. For there isn’t much to write home about. Overall government expenditure is budgeted to rise 7% YoY in FY26 over the revised estimate for FY25. This will be the third consecutive year of single-digit expenditure growth. And also the third consecutive year of expenditure growing slower than nominal GDP growth. Furthermore, if we exclude interest payments, government expenditure will grow below 6% YoY in FY26 as per the budget estimates. So while some departments and ministries and schemes will have seen higher allocation and some lower, on balance, the pie isn’t growing materially.

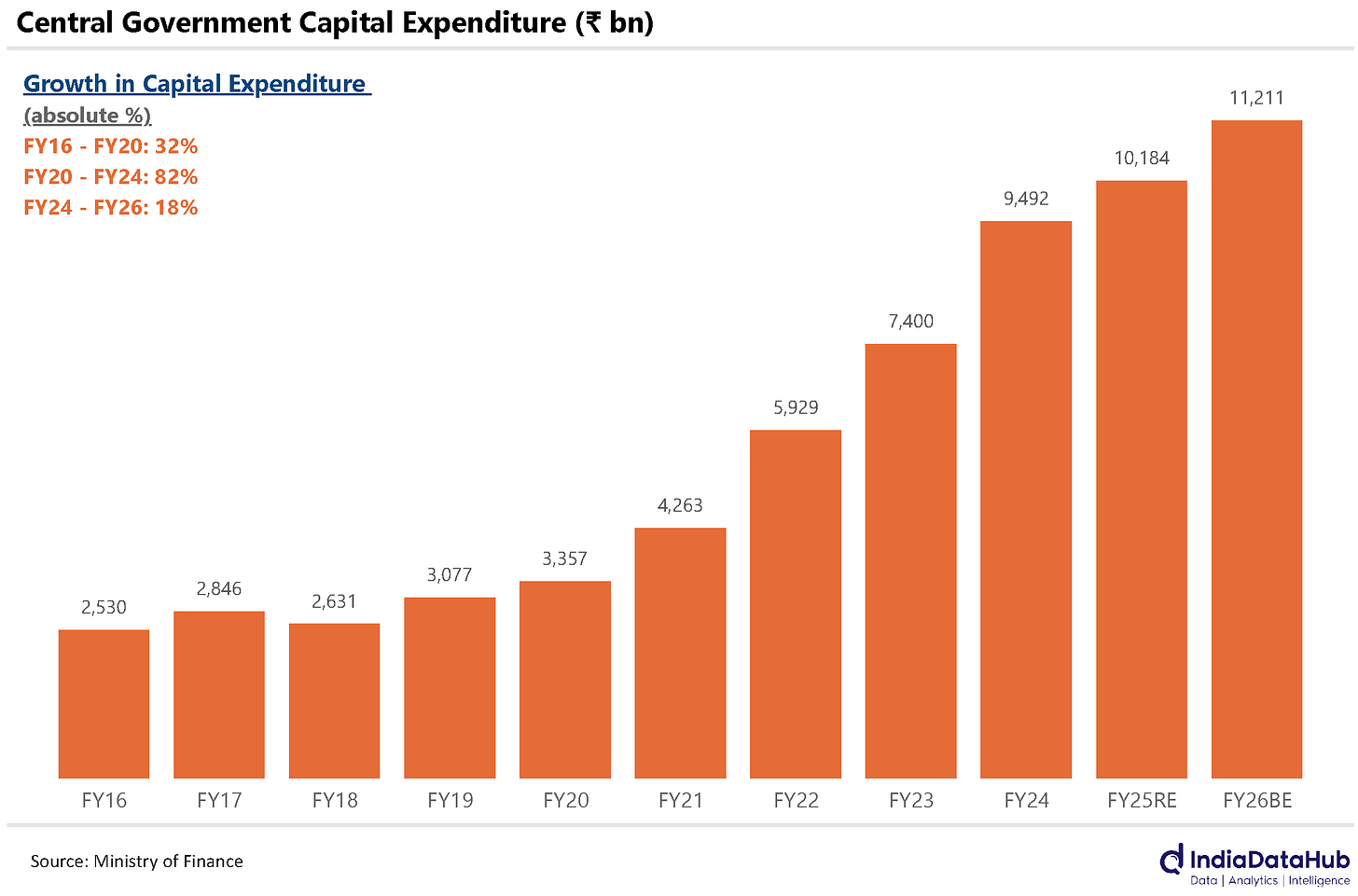

Part of the reason is that through the pandemic government expenditure and in particular capital expenditure expanded massively so it appears that there aren’t enough large schemes that can soak up additional expenditure. A good example of this is capital expenditure. The government has budgeted for a 10% growth in capital expenditure in FY26. However, most of this growth is due to higher loans that the government plans to give out – principally to states. And as we have been discussing in our monthly Fiscal Matters report, states have not exactly been going overboard on capex. Indeed, as of November, the aggregate capex of the 20 large states was down 4% YoY.

And this is in sync with the point that many have made that as far as investments are concerned, the government has pretty much done its bit in the last few years. For India to get into the 2003-07 kind of investment cycle will now require the private sector to chip in. From that perspective, the tax cuts to boost consumption demand make total sense. One can quibble over whether this is the right way to administer the medicine. A cut in GST rates for example would have benefitted a much larger number of people compared to a cut in the income tax rate – 50 or 60x more people. But then the flipside is that the benefit will get so diluted that people will hardly notice any potential benefit for them to alter their consumption pattern. So what the government has done is perhaps the more efficient approach.

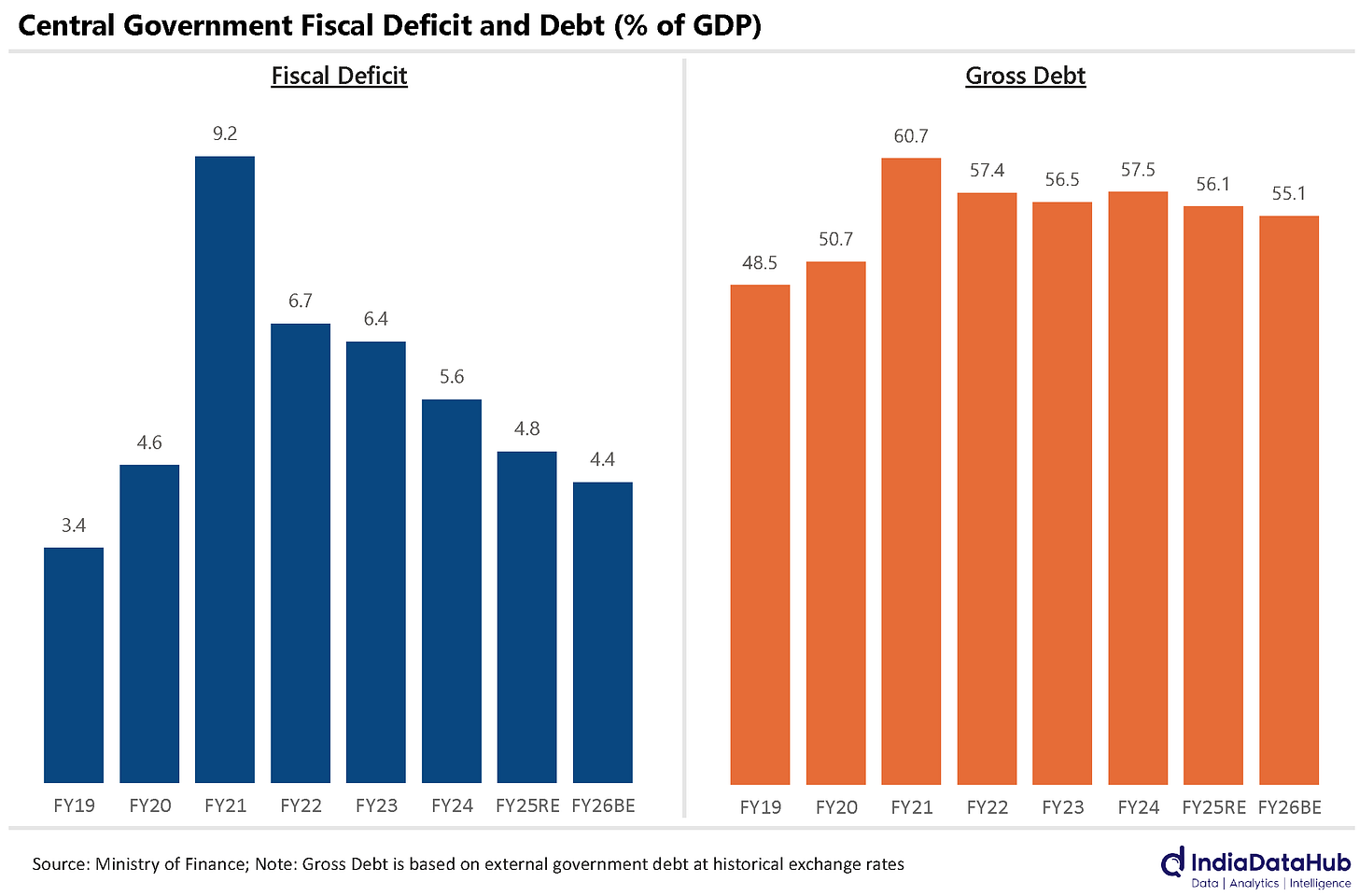

Last point on the budget, not all fiscal consolidations are the same. So in the next financial year, the government has budgeted for its fiscal deficit to decline by 40bps of GDP – from 4.8% of GDP as per the revised estimate for FY25 to 4.4% of GDP in FY26. In absolute terms, this translates to the fiscal deficit being unchanged in FY26 (₹15,689bn) from FY25 (₹15,695bn). However, despite this, the government’s net borrowings in FY26 are likely to be 10% higher than in FY25 as per the revised estimates.

In FY25 the government expects to borrow ₹10,427 from the market as per the revised estimates. This includes both dated securities as well as treasury bills on a net basis (net of repayments). However, in FY26 the government budgeted for a net borrowing of ₹11,538bn (dated securities as well as treasury bills). This is higher by ₹1,111bn or 11%. To be sure this is not any accounting gimmick. The government is anticipating a significant decline in small savings collections in FY26 which would need to be compensated through higher market borrowings. The crowding out effect of the fiscal deficit that we talk about is not so much due to the size of the deficit, but due to the amount of resources the government demands from the system and in FY26, it will increase, materially, as per the budget estimates.

The budget however may not be the focus for the markets in the near term. The markets have already reacted to the budget on Saturday(!) and they have bigger things to deal with. The first set of Trump tariffs have been imposed and retaliated against by both Canada and Mexico. A follow-up retaliation by the US is possible and it is anybody’s guess as to how this tariff war might end. And this is the backdrop that markets will open to tomorrow. The Budget is a relatively small event in that context.

It is also in this context that the RBI’s monetary policy committee meets next week. On one hand, is the volatile and highly uncertain global environment. Some of it has already played out through the exchange rate volatility. But another bout of volatility may perhaps be just around the corner given today’s global developments. And, on the other hand, is the budget which has boosted domestic consumption which should result in at least modest upgrades to growth estimates. Equally, higher consumer demand could easily impact inflation. So, in this environment it is not clear whether cutting interest rates is possibly the best course of action for the RBI given that while inflation has moderated, it hasn’t turned benign and risks have only increased.

That’s it for this week. Another eventful week beckons us. See you post that!

When analyzing any economic policy statement—whether it be the Annual Budget, Trade Policy, AI Policy, Employment Generation Policy, Monetary Policy, or any other economic directive—it is crucial to recognize that no policy can achieve inclusive economic growth through mere patchwork solutions addressing immediate problems. Without a strong foundation of social preparedness for the common good, such policies will inevitably fall short. If one seeks a true example of human prosperity, the present-day United States is not ideal. Instead, one should look to the Nordic countries, the U.S. of the 1960s, China’s rise in the 1980s, South Korea, or post-World War II Germany and Japan. History itself validates this trajectory of prosperity.