The 'Interim' surprise...

This Week In Data #51

In this edition of This Week In Data, we just cover the recently presented Union Budget for FY25. We will cover the initial few high frequency data for January in the next week’s edition when more data would also be available. So let’s get straight to the budget.

So the interim budget has come and gone. And while by most accounts the budget was positive. The government has budgeted for a further increase in capex on one hand and a further reduction in the fiscal deficit on the other. Just two days back we wrote about the Capex surge of the Central government. We wrote that the interim budget will likely budget for a further increase in capital expenditure relative to revenue expenditure. And that is indeed what has happened. The government has budgeted for an 18% growth in effective capital expenditure (including grants for the creation of capital assets) which will mean that over 30% of the government’s expenditure will now be for capex. At the same time, it has budgeted for the fiscal deficit to decline to 5.1% of GDP for FY25, the lowest since FY20 and a sharp 80bps moderation. More capex and less deficits – what else could one ask for?

So far so good. But the budget (in so far as the estimates or projections for FY25 are concerned) is largely irrelevant. This is for two reasons.

First, this being an interim budget, the incumbent government is generally expected to refrain from announcing major new schemes or changes in policies. As per protocol, that right is reserved for the new government which will present the full budget post the elections. So, even if the government wanted to announce new schemes or policies, it has refrained purely due to propriety. The FM hinted at precisely this in her post-budget media interactions.

The second is that the outcome of the elections itself will influence the contours of the final budget in July. And while the general expectation is that the incumbent government will come back to power, its margin of victory – whether higher or lower than expected – will also influence its policies. Similarly, if the incumbent government does not come to power, and while the odds for that appear to be trivially low they are not zero, and that will also influence the contours of the final budget.

But while the estimates for the next year are largely irrelevant, the revised numbers for the current year (FY24) are surprising on several counts. And the biggest surprise is that the Government expects tax revenues to come in below the budget estimate. This is being driven by an expectation of a sharp slowdown in tax revenues in the current quarter (4QFY24). Till December, the gross tax revenue has grown by 14.4% YoY. But the government is expecting this to moderate to just 8% growth during the current quarter. And by a higher-than-expected devolution of taxes to states.

However, despite this, and the lower-than-budgeted capital receipts (disinvestments!), the upside in non-tax revenues means that total receipts are expected to (modestly) exceed the budget estimate for the third consecutive year. And this means that the government is not under any material stress to economize. Or to cut back on expenditure. It could spend what it had budgeted and meet its deficit target.

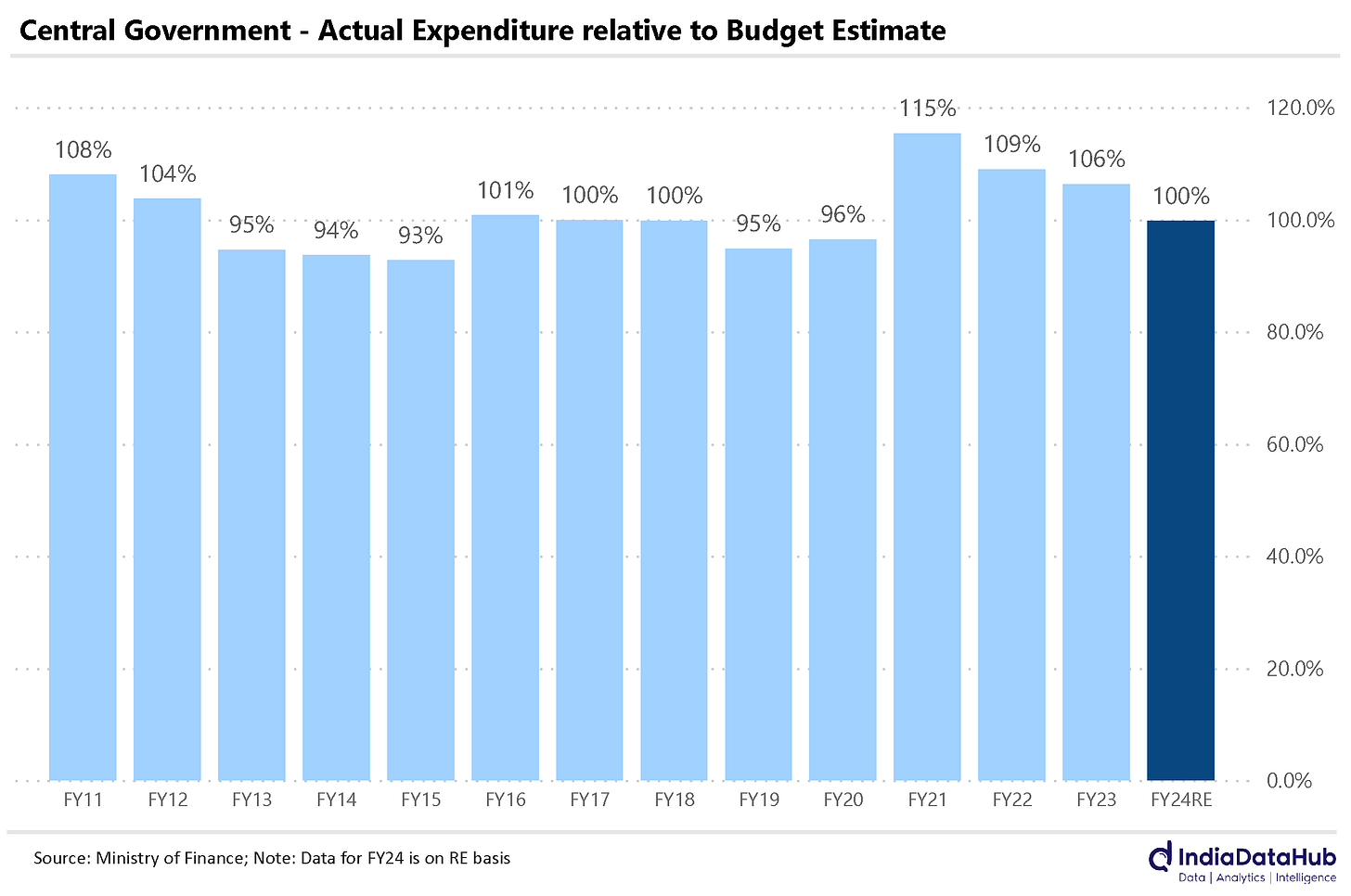

And in aggregate that is what the government is doing. The revised estimate for total expenditure is only marginally lower than the budget estimate – the revised estimate for total expenditure is 99.7% of the budget expenditure (just ₹126bn lower in absolute terms). So, in aggregate, the government is NOT economizing. And yet, the expenditure pattern for the year is significantly different from the budget estimate. There are several heads of expenditure where the spending is likely to be much more than budgeted and consequently, several heads of expenditure where spending will have to be cut back.

Before we analyze the sectoral divergences, it is worth noting that the Government follows the cash system of accounting. This means that it recognizes something as an expenditure only when it releases the money. And that gives the government significant flexibility in how it wants to manage spending in any given year. So, the divergence in actual spending relative to budget estimates is for the most part a conscious choice.

So which areas is the government spending more on this year? It is largely revenue expenditure and specifically a few heads within it. Overall government’s revenue expenditure is expected to be higher than the budget estimate by ₹380bn. But the increase is driven by 5 key heads – Subsidies, Defense (revenue expenditure), Education, NREGA and Agriculture Infra Fund. These 5 heads account for a cumulative increase in revenue expenditure of ₹1300bn. On the flip side, there has been a significant reduction in grants to the state (almost ₹750bn) relative to the budget estimate which has offset some of this increase in revenue expenditure.

But by far the biggest surprise has been a reduction in capital expenditure. The revised estimate for capital expenditure is for a 5% or ₹500bn reduction in capital expenditure relative to the budget estimate. And most of the reduction in the grants to states is in grants for capital expenditure. Consequently, the effective capital expenditure has seen a reduction of almost ₹1000bn or 7% relative to the budget estimate. The biggest casualty has been the states which have seen a significant reduction in grants for capital expenditure as well as a reduction in loans and advances. And this will in turn reflect in the lower state government’s capital expenditure.

There are two implications of this. The first implication is that the expenditure patten indicated in the budget is at best a statement of intent. Even in a year when the government does not have to economize and cutback on expenditure, its actual expenditure (as proxied by revised estimate) in in some sectors materially different from what was budgeted. Something to note before we analysts change our GDP numbers or inflation projections or earnings estimates on the back of mere announcements😊.

But more fundamentally, it raises the question as to why the government had to cut back on capital expenditure when it does not seem to be facing a particularly challenging political situation. Whether the lower capex was forced due to the higher revenue expenditure or whether the higher revenue expenditure is an outcome of inability to spent on capex. This is a bit of chicken and egg which only the FM can help answer. But if the answer is the former, then it is less of a worry as the government can do a reset post-election.

But if it is the latter, it would suggest that the government has kind of reached a peak in terms of how much capex it can do. After all, its effective capital expenditure has increased almost 2.5x in just the last 4 years (even after the downward revision in the current year). This would suggest that the constraint is no longer money, but the availability of schemes and programs that can absorb that money. And so, the onus of continuing the capex cycle will then fall to state governments and the corporate sector.