Weak Growth, Hazy Fisc, Liquidity and more...

This Week In Data #103

In this edition of This Week In Data, we discuss:

GDP Growth sees a sharp slowdown

Central government’s capex declines again in October

Tax collections continue to remain weak

Falling small savings inflows

Euro area CPI ticks up

US GDP growth remains strong in 2Q

Bank of Korea starts to ease monetary policy

In case you missed, we released several multilateral datasets earlier this week. Multilateral datasets facilitate cross country comparisons by providing consistent long time series data. In all we track these data sets for over 100 countries and country groups with history going back to several decades in most cases. This video gives a quick overview of the same.So, the GDP growth has slowed sharply to 5.4% during the September quarter. This is down from just under 7% YoY growth during the June quarter and almost 8% growth during the September quarter last year. This is also the slowest growth since the December quarter of 2022.

At a very high level, the quarterly GDP growth rate is practically irrelevant. It is akin to getting the bill at the end of your meal in a restaurant – you knew what you were ordering and what the cost was when you went through the menu. So, by the time you are done with your dessert, you already know what you would owe the restaurant. In the same way, most of the data which goes into the estimation of quarterly GDP was already available (and it pointed to a marked deceleration in growth). Corporate earnings have been disappointing, and analysts have already cut the full year’s profit estimates. So, there is not much follow-through implication of this weak number – except the noise in financial media.

This is not to say that the quarterly GDP release is entirely irrelevant. The most important implication of the weak GDP print will be monetary policy. For the first half of the year, GDP has grown by ~6% (or slightly higher if you look at the GVA numbers). And for the full year, the RBI has projected growth of over 7%. This implies over 8% GDP growth in 2H which looks highly improbable as of now. RBI’s reluctance to cut interest rates so far has been premised primarily on the fact that it estimated growth to hold up strong. And even as that pillar is now looking shaky, inflation has crossed 6%, albeit most likely temporarily. So, when the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meets next week, it faces a complex situation – perhaps the most complex in recent history.

And it boils down to a simple question – was the growth slowdown in 2Q a blip or will growth remain weak in 2H also? In terms of data, we will get some of the high-frequency data for November next week and that will tell us how some of the data, especially consumption-related, has been through the festive season. The other factor that will influence growth will be government spending.

October saw an over 30% YoY increase in the Central government’s expenditure. And this was entirely driven by higher revenue expenditure. Capital expenditure declined by 10% YoY in October. This is the third consecutive month that the centre’s capex has declined. More importantly, the growth in tax revenues was weak. Gross tax revenues grew by just 2% YoY. Corporate as well as personal tax collections declined in October. Over the past 3 months tax collections, in aggregate, have grown by less than 1% YoY. At this rate, the full-year tax collections estimate will be missed by a wide margin and this will warrant lower than budgeted full-year expenditure.

The hazy fiscal picture also complicates the liquidity situation. One of the key sources through which the government funds its fiscal deficit is the small savings inflows. And so far this year, they have seen a sharp decline. In October the inflows under small savings declined by 25% and in the first 7 months of this financial year, net inflows have declined by 30%. At this rate, small savings inflows will be almost ₹930bn lower than the budget estimate and this will require commensurately higher market borrowings.

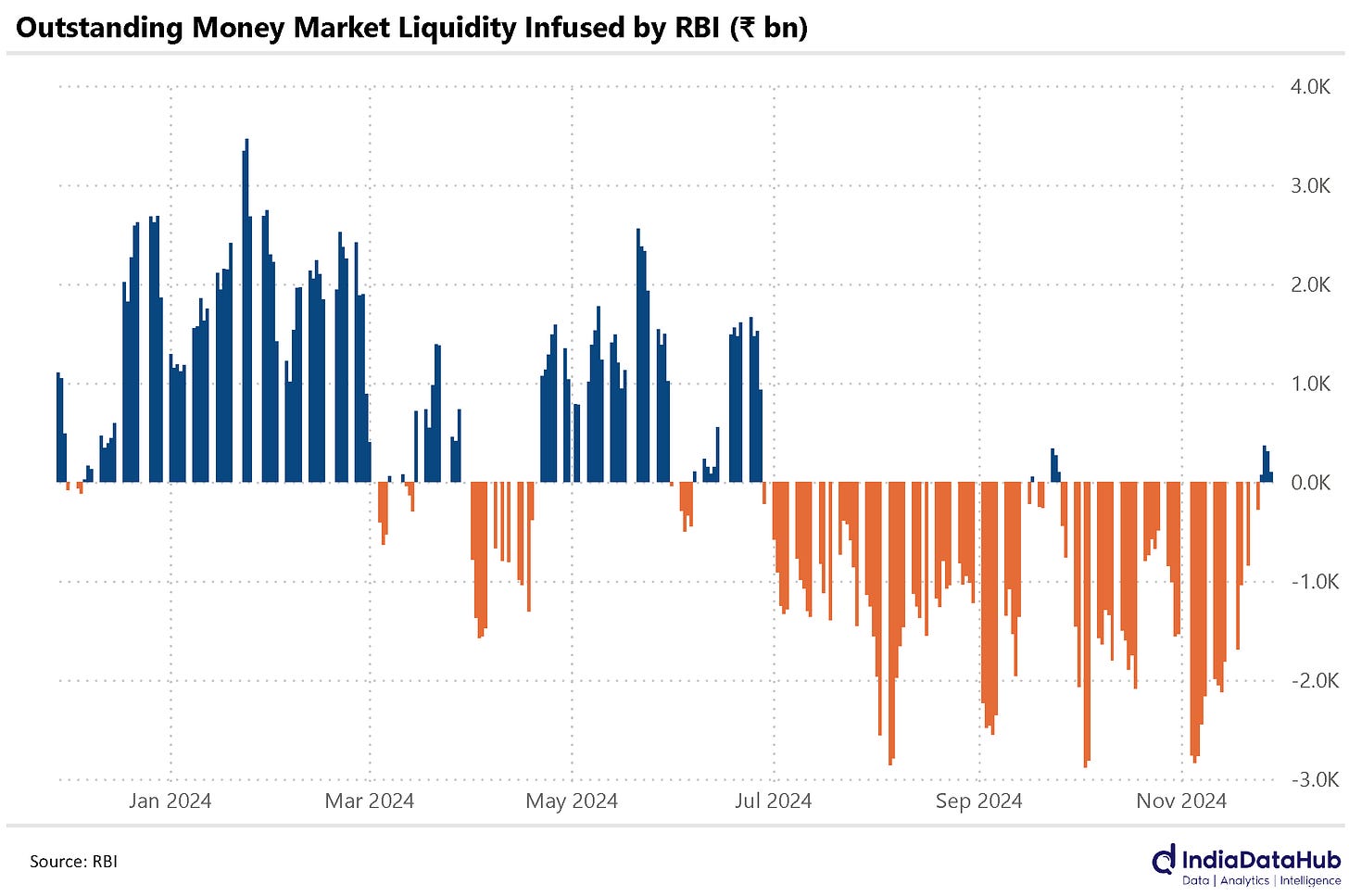

This will complicate the domestic liquidity situation. This will happen at a time when due to the capital outflows, the RBI is defending the rupee which is also net negative for the domestic liquidity – RBI is providing dollars to the market on one hand and taking away rupees. Currently, the money market liquidity has reverted to being in balance after being in large surplus since June.

In summary, the domestic economy has suddenly hit turbulence. And the pilots of the economy (the RBI and the Government) will now have to disengage the autopilot and fly manual! On that sombre note, let us turn our attention to global data flow.

The Euro area CPI rose 30bps to 2.3% in November as per the flash estimate. Euro area HICP is now at a 4-month high. The services sector is the biggest driver of the HICP rising 3.9% YoY followed by Food, Beverages, & Tobacco which is up by 2.8%.

The US Bureau of Economic Analysis released the first revised estimate of GDP for the September quarter and the growth estimate was unchanged at 2.8% Saar, down only slightly from the 3% Saar during the June quarter. Lastly, the Bank of Korea is the latest central bank to ease monetary policy. It cut its policy rate, the base rate, by 25bps to 3%.

That’s it for this week. See you next week.